Last Tuesday, Georgia secretary of state Brian Kemp scored a come-from-behind victory over Lieutenant Governor Casey Cagle in the Republican gubernatorial primary runoff. As Charles Bullock, the University of Georgia’s Richard B. Russell Chair of Political Science, has recently observed, Kemp’s margin of victory represented a swing of 43.9 percent from the primary to the runoff—a new Georgia election record. Kemp now advances to the general election where he faces former Georgia House minority leader Stacey Abrams and Libertarian Ted Metz in what promises to be one of the most expensive and closely watched races in the 2018 election cycle.

An Athens native, Brian Kemp graduated from Clarke Central High School and the University of Georgia. Prior to becoming secretary of state in 2010, he represented Athens in the State Senate from 2003 until 2007. His grandfather, Julian H. Cox, Sr., served in both the Georgia House of Representatives and State Senate during the 1950s and 1960s. His father-in-law, Robert E. Argo, Jr., represented Athens in the House from 1977 to 1987. Unlike Cox and Argo, though, Brian Kemp is a Republican.

Brian Kemp is also the first serious gubernatorial contender from the Classic City since Athens attorney Abit Nix waged two pitched campaigns against Eugene Talmadge in 1932 and 1940.

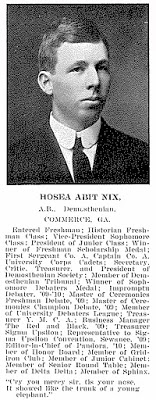

Hosea Abit Nix was born near Commerce in Jackson County where his father was a well-to-do farmer, county commissioner, and state senator. Nix moved south to attend the University of Georgia where he graduated with an A.B. in 1911 and an LL.B. in 1912. Nix continued his legal studies at University of Chicago and Harvard, but he returned to Athens in 1913 to work and teach at his alma mater. Nix became a prominent Athens attorney rising to the rank of partner in the local firm of Erwin, Erwin & Nix (subsequently Erwin, Nix, Birchmore & Epting).

Aside from his teaching and professional duties, Nix belonged to a dizzying array of fraternal and civic organizations such as the Elks, Moose, Freemasons, and Shriners. He was also a founding member of the Rotary Club of Athens, and he served as a club president, district governor, international director of that organization at various points in his career.

In 1932, Governor Richard B. Russell Jr. opted to run for the United States Senate rather than reelection. This triggered a free-for-all in that year’s Democratic gubernatorial primary. Agriculture Commissioner Eugene Talmadge, espousing his signature brand of reactionary populism, emerged as the frontrunner. The centerpiece of Talmadge’s 1932 campaign was a promise to sell automobile tags for a flat, three-dollar fee—a pledge immortalized in song by Fiddlin’ John Carson and Moonshine Kate.

Nix, drawing heavily on his civic background and legal experience, launched his own gubernatorial campaign in May 1932. Nix could not hope to match Talmadge’s personal flamboyance and populist fervor so he sought to compensate with sober policy prescriptions, which he outlined in a lengthy, twelve-point platform. In it, he pledged “efficiency, economy and honesty” in government, the “elimination of waste and extravagance” in state affairs, and improved roads and schools. That message carried Nix to a respectable second place finish in 1932. Amassing just over 28 percent of the popular vote to Talmadge’s 42 percent, Abit Nix ran best in the urban centers and college towns the rural-oriented Talmadge disparaged so gleefully on the campaign trail.

Unlike that year’s other aspirants, Nix generally avoided attacking Talmadge directly. Instead, he railed against “professional politicians,” a distinction that included Eugene Talmadge as well as former governor Thomas Hardwick and State Highway Board chairman John Holder. Nix’s 1940 campaign for governor, however, was an entirely different matter altogether.

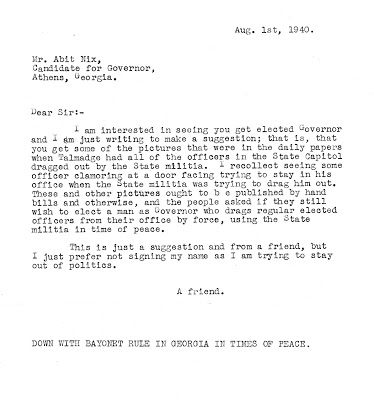

Eugene Talmadge, having been rebuffed by voters in back-to-back bids for the U.S. Senate in 1936 and 1938, was seeking a third term as governor that year. Talmadge had demonstrated a penchant for spectacle, demagoguery, authoritarianism during his two previous administrations. When the General Assembly balked at Talmadge’s “Three-dollar tag” in 1933, he lowered the fee by executive order. When the State Highway Department refused to comply with various demands, Governor Talmadge seized the department’s funds, ejected the board from office, and appointed loyalists who would do his bidding. Most controversial of all, perhaps, was Talmadge’s response to the United Textile Workers strike in September 1934. The governor declared martial law, dispatched the National Guard, and arrested pro-union picketers to quash the protest. The jarring images of bayonet-wielding guardsmen and labor activists incarcerated behind barbed wire at Fort McPherson dismayed Talmadge critics who worried the governor’s heavy-handed style flouted the rule of law and tarnished the state’s reputation.

Abit Nix launched his second campaign for governor in June 1940. Present as always were Nix’s acclamations of “honesty, efficiency and economy,” but he also denounced—constantly and vigorously—Eugene Talmadge in the most unflattering terms. “The people don’t want a blitzkrieg governor again,” Nix declared, referencing the style of warfare Nazi Germany was employing with terrible effect across Western Europe that summer. “I am making the fight to put our government on a common sense, democratic basis where law and respect of constituted authority shall prevail over the wishes of political officials armed with the bayonet.”

The race, which also featured Agriculture Commissioner Columbus Roberts, grew increasingly nasty in the run up to the September Democratic primary. A fistfight between Talmadge and Nix supporters erupted at one Warm Springs gathering when a fashionably late Eugene Talmadge arrived just in time to interrupt Nix’s stump speech. The tumult flared back up when Talmadge took the stage, and by the end of the day, a wheelchair-bound man had reportedly been hospitalized and an automobile torched. Both sides traded blame for the donnybrook, and Nix persisted in comparing his primary opponent to German chancellor Adolf Hitler for the remainder of the campaign.

For his part, Eugene Talmadge offered a more progressive platform and milder image in 1940 than he had in previous campaigns. Most historians now credit Herman Talmadge, Gene’s son and political heir, for smoothing his father’s rougher edges that year. Combined with incumbent governor E.D. Rivers’ numerous scandals and a divided opposition (which Talmadge exploited deftly), “Ole Gene” cruised to victory while Abit Nix ran a distant third.

Talmadge, however, reverted quickly to his old ways when he instigated a purge of college administrators, teachers, and University System of Georgia regents on trumped up charges of advocating “communism or racial equality” in the summer of 1941. The original and most high-profile target of Talmadge’s ire was University of Georgia College of Education dean Walter Cocking. (Cocking served with Nix in the Athens Rotary Club.) Talmadge’s political interference in what became known as the “Cocking Affair” cost all state-supported white colleges and universities their accreditation, and it cost Talmadge reelection in 1942. Improbably, Talmadge would make one, final political comeback in 1946. But that’s another story entirely.

Throughout his political career, Abit Nix was one of those Georgians who was, in the words of esteemed political scientist V.O. Key, Jr., “damned with the designation of ‘respectable.’” There is perhaps no clearer example than Nix of what another scholar, Joseph Bernd, dubbed “the best element” in Georgia politics. “The member of ‘the best element’ is the sort of person who places a high priority on high moral standards of official conduct, believing that the method of government aside from questions of policy, is important in its own right.”

Unfortunately for Nix and those subscribing to his political brand, he never had the opportunity to implement his vision. Abit Nix died in March 1959 at age 70. Harold Martin, an Atlanta Constitution columnist and editor who had volunteered on Nix’s 1932 campaign, reflected on the Athenian’s inability to break through with voters. “In that time…people didn’t want the quieter virtues in their candidates for governor. They wanted to see a showman on the stump, a ranter and snorter, a leaper and shouter. Abit Nix, somehow, just didn’t have it in him to play the demagogue.” To Nix, respectability in personal decorum and political affairs weren’t simply preferable—they were essential elements.

The Richard B. Russell Library houses a collection of papers and artifacts related to Abit Nix’s political career and civic activities. His unsuccessful 1940 gubernatorial campaign is extensively documented. Researchers will gain particular insight into Mr. Nix’s rationale for launching his campaign as well as his supporters’ political attitudes and outlooks. The Russell Library also holds the papers of state representative Bob Argo as well as the Rotary Club of Athens records.

N.B. If elected, Brian Kemp would become the first native Athenian to hold that office. Two other prominent residents, Wilson Lumpkin (1831-1835) and Howell Cobb (1851-1853), have served as governor, but neither were born and raised in Athens.

Ashton Ellett